The Lumbar Disc Herniation & Hockey Athletes

I was once a hockey player.

I played the game for over a decade and many of those years at a competitive level. To this day, I still play, but only at a recreational level. I gave up chasing the dream many years ago to pursue an education in Exercise Science.

Shortly after giving up playing hockey competitively, I got involved in CrossFit style workouts, some heavy strength training, as well as still playing hockey 1-2x a week recreationally. With this combination, and already having over a decade of hockey experience under my belt, it was only a matter of time until something may have given out. In late 2013 I had developed some severe lower back pain after a poorly executed deadlift, and things were made worse while continuing to play hockey, as well as performing some ill-advised exercises afterwards. By January of 2014, I officially had an MRI showing an L5-S1 Disc Herniation (disc protrusion) and a mild amount of osteoarthrosis at all of my lumbar facet joints.

All of this at the age of 20 years old, you could say my low back was pretty beat up for a young guy.

A little while after this I got involved in the field of strength & conditioning and did an internship with the Windsor Spitfires and Drive Performance organization. During this internship, I was working primarily with hockey players that ranged all the way from competitive minor league hockey to the NHL. Interestingly, during my time interning/working with the Windsor Spitfires and Drive Performance, one hockey player, in particular, had some severe low back discogenic issues (herniated disc at L4-L5 & L5-S1) and had surgery done to repair those issues.

While I was still going through my recovery at the time (doing my self-rehab) and was extensively learning about low back injuries, this was the first individual I had ever worked with that had some severe lower back problems. It was a very cool experience at first because I could relate to what this athlete may have been previously feeling before his surgery and what some of his current limitations were at the time. This made it easier for me to coach this athlete through exercises, as I knew what would potentially trigger and not trigger his lower back pain. In a sense, going through a similar injury to this athlete made me a better coach as I could specifically relate to what this athlete may be experiencing.

That was a bit of my introduction to lower back injuries, as well as were things first started for me regarding working with athletes that had severe lower back troubles. Since, that experience, almost 5 years have gone by, and I’ve learned a lot more then I could ever imagine about lower back injuries, as well worked with a wide variety of individual’s trying to work around a lower back injury.

Now, rather than share my whole journey about my recovery and working with several individuals with low back issues, I want to talk about why so many hockey players may end up with low back problems from a lumbar disc herniation, as well as share some strategies for preventing this injury. While many different low back injuries may develop in hockey players, the most common and one of the most severe is the lumbar disc herniation. In this post today, I am going to dive deep into the lumbar disc herniation in hockey players.

The Lumbar Disc Herniation in Hockey Players

Unfortunately, the lumbar disc herniation has ended some hockey player’s careers, and many that develop a lumbar disc herniation that may be able to come back aren’t ever the same. Nathan Horton’s career was ended due to some severe discogenic problem’s, and it’s honestly a sad story. Joffrey Lupul is another player whose career was never the same after surgery to repair a herniated disc. However, if you look to other players that have had a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation and were able to return, such as Zach Parise, Jason Spezza, Daniel Alfredsson, and Marian Hossa, their performance was not the same before their injury. While these are some household names, there is actual research to support this observation.

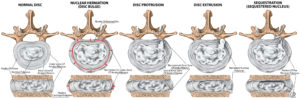

The above photo represents different classifications of disc herniations. Licensed from “stihii/Shutterstock.com.”

Schroeder, McCarthy, Micev, Terry, and Hsu (2013) examined the performance scores (e.g., games played, goals, assists, points, even strength goals, power play goals) of a total of 87 NHL players between the years 1967-2009 who suffered a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation and their return to NHL action. Of these 87 NHL players, 31 underwent conservative treatment, and 56 underwent surgical treatment (48 with a discectomy: 8 with a single level fusion). 85% of these NHL players that underwent conservative treatment or surgical treatment were able to return to play, but the capacity to return was horrendous.

- Average games played dropped from 56.2 (preinjury) to 39 (post injury)

- Averages point per game dropped from 0.22 (preinjury) to 0.17 (post injury)

- Performance score dropped from 0.79 (preinjury) to 0.46 (post injury)

Based off these statistics reported by Schroeder et al., (2013), the return to play after a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation is not good for NHL players! Preventing lumbar disc herniation’s are critical if any hockey players plan on having a long and high-performing career.

Now that we understand some of the serious implications of a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation in professional hockey players from Schroder et al., (2013) research, the next question is – how do these injuries develop in the first place?

Well to understand, we must look at the sport of hockey itself and the way it’s played.

The Sport of Hockey

Hockey can be a hazardous sport, and most people know this, just like any other sport, but what most people don’t know is how it can be “very” dangerous to your lower back. When you look at the biomechanical features of playing the sport, you’re constantly involved in various flexed lumbar spinal positions, whether that’s when your skating, shooting a puck, sitting on the bench, carrying a hockey bag on your shoulder or lacing the skates up.

Not to mention, hockey players are on the ice just about every day in-season and sometimes twice a day if there is a morning skate. By doing this, they’re constantly breaking down the tissues in their lumbar spine and potentially putting themselves at risk of injury. The mechanism for creating a lumbar disc herniation is repeated cycles of lumbar flexion under compressive load (Callaghan & McGill, 2001).

Also, to make matters worse, tall hockey players are the ones that get beat up the most since their levers are so long and it’s harder for them to bend. It’s no surprise that tall hockey players like Mario Lemieux, Jason Spezza, Martin Hanzal, Ilya Kovalchuk, and Eric Fehr developed severe discogenic problems that limited their careers.

While the sport of hockey itself is a major factor in “why” so many hockey players develop low back problems, I see the weight room as an “area” where things often go wrong.

A poorly designed exercise program that may include exercises like sit-ups, deadlifts with poor technique, or any activity that may take the spine through a full range of motion (flexion) under load is a serious concern. As mentioned above, the mechanism for creating a disc herniation is repeated cycles of lumbar flexion under compressive load (Callaghan et al., 2001). Note: Flexion combined with twisting will make things significantly worse if added into the equation.

Repeated Cycles of Lumbar Spinal Flexion in the case of a sit-up is the mechanism for creating a lumbar disc herniation. This is a reason why sit-ups are not a part of the NHL combine anymore, as well as the Canadian Military Fitness testing.

Performing deadlifts with poor technique as indicated in the photo above are the exact reason “why” so many individuals end up with disc herniations. Many hockey players tend to lack hip mobility making it very challenging for them to deadlift safely from the floor.

I can tell you that as someone who has suffered from a disc herniation injury, it’s not a fun experience and can be severely limiting. Preventing a lumbar disc herniation injury should be a priority in any strength & conditioning program.

So, now that we know the mechanism for a lumbar disc herniation is repeated cycles of lumbar flexion under compressive load (e.g., sit-ups, poor deadlift technique) – the question now becomes:

How Do We Prevent This Injury From Developing in Hockey Players?

1. Become Educated

Well, first in foremost, it’s important to be educated about the topic. Players and especially strength coaches/trainers need to understand what is good versus poor spinal positioning. From here, if players understand this, they can potentially implement this into their daily life and reduce the number of times they put themselves into highly stressful low back spinal positions.

An example could be seen when tying your skates with a ‘neutral spine’ (straight spine), as opposed to a fully flexed spine. Often you will hear hockey players throw their low back out when trying to tie their skates, and this is a direct result of moving into a poor spinal position that is very stressful on the low back. Ultimately, by doing little things like this over the course of the day, one can reduce the amount of stress placed on the low back and potentially spare their spine of injury.

The left photo represents poor skate tying posture. The right photo represents good skating tying posture that helps spare the low back. Hockey players with existing or previous low back problems may be wise in adopting this spine sparing skate tying technique.

The left photo represents a common way hockey players carry a bag that is more stressful on the low back when compared to the photo on the right. (Note: You will almost always notice a low shoulder on the side a hockey player carries their bag). The right photo represents a spine sparing posture that involves dragging a hockey bag on wheels similar to a suitcase. Hockey players looking to spare their dominant shoulder and low back may be wise to adopt this technique.

2. Avoid Ill-advised Exercises & Perform More Spine-Sparing Exercises

Avoiding exercises like sit-ups, barbell bent over rows, leg presses, and incorporating more spine sparing exercises (e.g., standing single arm cable row, bird-dogs), as well as core stability exercises (e.g., planking variations, suitcase carry), would be very important. Sit-ups, barbell bent over rows, and leg presses are examples of exercise that I believe are very high risk for hockey athletes to be performing. I would never prescribe these exercises to an athlete that is at risk for such lower back troubles or for anyone that currently has lower back issues. On the flip side, implementing more spine sparing exercises and core stability exercises would be very important in reducing the low back injury potential.

The above photo represents the classic “leg press” exercise. Athletic hockey performance cannot be trained in a seated position and the “leg press” can place high stresses on the low back. This is not a machine/exercise that would be in a hockey players best interest to be performing. The arrow indicates a common technique flaw known as “butt wink” and is commonly seen with folks performing the leg press or squat.

The Single Arm Cable Row is a great exercise for sparing the spine, developing rotatory stability and strengthening the upper back.

The suitcase carry is an advanced lateral core stability exercise that many hockey players may benefit from performing.

3. Follow an Individualized Strength & Conditioning Program

Do the right things in the weight room, and you may potentially add a few years to your career or even improve your performance on the ice. However, do the wrong things in the weight room, and your career could be cut short due to a severe lower back injury. This is why strength & conditioning coaches exist.

Hockey players, for the most part, don’t know what they should be doing or shouldn’t be doing in the weight room because if they did, then myself and many others would be out of a job. The whole point of strength & conditioning is to help an athlete prevent injury and improve their performance. Investing in a good strength coach that knows the sport of hockey and knows lower back injuries could be one of the best investments a hockey player could make.

4. Avoid Early Morning Spine Bending and Workouts

As a hockey player, working out later in the morning or afternoon may be a wise option. The bending stresses on the lumbar spine are about 3x higher in the early morning (first 1-2 hours) when compared to later in the day (Adams, Dolan & Hutton, 1987). Our spinal discs are like fluid-filled balloons ready to pop in the morning, which creates more annular tension and a stiffer spine.

As a hockey player, if you start doing bending activities in the early morning, specifically right after you wake up, you could be asking for some significant low back trouble. If you don’t have the option to workout later in the morning or day, it would be very important to perform an extensive warm-up that may involve walking for 10-20 minutes before weightlifting, as this will help reduce some the fluid content in the spinal discs.

Conclusion

There is a lot that hockey players can due to ultimately avoid lumbar disc herniations, and these are just a few important considerations I mentioned above. If you can follow these points above or begin to learn about the spine, it can go a long way in preventing a serious spinal injury from occurring. Trust me, having gone through the injury myself; it’s not something you want to experience. It took me close to 3 years to return to playing hockey regularly again at a recreational level! As noted above, some players haven’t even been able to return and may still be in pain. This is not an injury to fool around with.

Salute,

Remi

References

Adams, M. A., Dolan, P., & Hutton, W. C. (1987). Diurnal variations in the stresses on the lumbar spine. Spine, 12(2), 130-137.

Callaghan, J. P., & McGill, S. M. (2001). Intervertebral disc herniation: Studies on a porcine model exposed to highly repetitive flexion/extension motion with compressive force. Clinical Biomechanics, 16(1), 28-37.

Schroeder, G. D., McCarthy, K. J., Micev, A. J., Terry, M. A., & Hsu, W. K. (2013). Performance-based outcomes after nonoperative treatment, discectomy, and/or fusion for a lumbar disc herniation in national hockey league athletes.The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(11), 2604-2608.