What I’ve Learned From My Experience Dealing with Facet Joint Osteoarthrosis

Osteoarthrosis, also known as degenerative joint disease is a condition I was diagnosed with a little over 4 and a half years ago after undergoing an MRI on my lumbar spine. The osteoarthrosis was a mild case and seen at all of my lumbar facet joints at the age of 20 years old. While the L5-S1 disc herniation was always the primary issue I was dealing with, the facet joint osteoarthrosis was a secondary condition that would cause me some issues from time to time throughout the years.

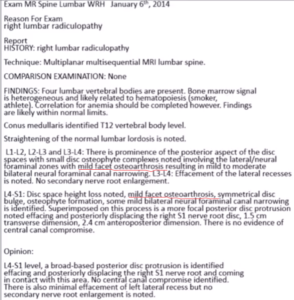

Mainly, prolonged periods of sitting and heavy squatting have been two tasks that have been a bit of a struggle at times. In the photo below is a picture of my MRI report that was taken on January 6th, 2014 which is where I was first initially diagnosed with facet joint osteoarthrosis.

In the above photo is my MRI report from January 6th, 2014. Notice the mild facet osteoarthrosis as underlined in red.

Growing up I had always perceived osteoarthrosis/osteoarthritis as a condition you get with old age. If you look to western culture, television commercials are always promoting osteoarthrosis/osteoarthritis relief products to older adults. As a result of being repeatedly exposed to these advertisements over the years, the association between old age and osteoarthrosis/osteoarthritis became ingrained in my beliefs.

I truly believed when I was a young fellow that only older adults develop osteoarthrosis/osteoarthritis and never did I think a young individual like myself could have this condition at the age of 20.

With that being said though.

I’ll never forget the day when my family doctor was going over my MRI report with me, and he mentioned:

“Your too young to have this condition.”

I thought my future was doomed when I had heard this.

I can tell you that it’s not a pleasant experience being told you have a degenerative condition at a young age of 20 years old that supposedly only “elderly” people get.

However, from what I’ve learned over the years, osteoarthrosis (degenerative joint disease) is not necessarily an elderly’s persons disease as it’s made out to be.

For instance, Alyas, Turner & Connell (2007) took MRI scans of the lumbar spine in 33 elite level tennis players without a history of low back pain (average age 17 years old) and found that 70% presented with a case of asymptomatic facet joint arthropathy (joint disease). For 70% of elite tennis players to have some form of degeneration (while asymptomatic) in their facet joints at the age of 17 years old, clearly shows that “age” is not necessarily the driving factor for this condition.

Rather, there are other important variables at play for osteoarthrosis to develop, and that leads me to the question:

What Exactly is Osteoarthrosis?

For those that aren’t familiar with the term osteoarthrosis, it’s simply a condition to describe changes to the joint as a result of mechanical overloading, avascular necrosis (cell death), previous injury/disease sustained and metabolic changes (Tanchev, 2017). The term osteoarthrosis is often misinterpreted as osteoarthritis, and there are 2 distinct differences between the terms, as professor Pavel Tanchev mentions in his reconstructive review of the terms osteoarthritis and osteoarthrosis:

“The term “osteoarthrosis” is correct for degenerative joint disease. Inflammation may play only a secondary or concomitant role in this condition. This is in contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, which is primarily an inflammatory pathologic entity. In short, “osteoarthritis” means inflammation of the joint, while “osteoarthrosis” means degeneration of the joint.”

The suffix “itis” implies inflammation, whereas the suffix “osis” implies the change of a structure or deformity. A very subtle difference between the terms and it can often confuse many who do not understand the semantics of each. In English literature, many may refer to osteoarthritis as degenerative joint disease, but as professor Tanchev mentions, osteoarthrosis is the correct term for degenerative joint disease and not osteoarthritis. This is why both osteoarthrosis and osteoarthritis may become very confusing to many who aren’t familiar with the terms.

While the semantics can be different, it’s important to note that osteoarthrosis is a result of mechanical overloading, avascular necrosis, previous injury/disease sustained and metabolic changes to the joint (Tanchev, 2017).

In my case, I had a mild amount of degeneration at all my lumbar facet joints, which I’d consider a result of all the wear and tear I accumulated over the years. Note: The video below portrays a visualization of what my lumbar facet joints probably looked like 4 and a half years ago, as well as today.

I can tell you that years of playing hockey combined with poor exercise training took a significant toll on my low back at the age of 20.

I mean to be quite frank… how many people do you hear develop some form of osteoarthrosis at the age of 20?

Not very many I would bet, and I was one of the unfortunate ones I guess you could say.

Now, to better understand the osteoarthrosis I was dealing with, as well as how it potentially developed, we need to understand the function and anatomy of the facet joints.

The Facet Joints

The facet joints are synovial joints that help in the movement of the spine by flexing, extending, laterally flexing and rotating the spine (Nielson & Miller, 2008). Also, while helping with movement, the facet joints play a role in the management of compressive, shear, tensile, bending and torsional forces through the spine. The facet joints and discs provide about 80% of the spine’s ability to resist rotational torsion and shear, with more than half of this contribution from the facet joints (Jaumard, Welch, & Winkelstein, 2011; Skrzypiec et al., 2013).

The Facet Joints play a significant role in helping with flexion and extension movements of the spine, as well as small amounts of rotation and lateral flexion (Nielson & Miller, 2008). Each vertebra has a pair of facet joints that are located on the posterior side of the spine (Nielson & Miller, 2008). Image licensed from “AlexeyBlogoodf/depositphotos.com.”

Yang & King (1984) reported that normal facet joints carry about 3-25% of the compressive load on the spine, whereas degenerative lumbar facet joints may absorb up to as high as 47% of the compressive load on the spine. Degenerative facet joints will create instability of the spine, and this may alter the way compressive forces are administered through the spine (Cailliet, 2003).

Dunlop, Adams & Hutton (1984) reported that forces acted upon human cadaveric lumbar facet joints increases when the lumbar spine is placed into increasing degrees of extension, and disc height loss is present. Shirazi-Adl and Drouin (1987) found that the facet joints carry as much as 30% of the compressive load in the presence of 2° to 5.6° of extension rotation. The highest compressive loads on the facet joints tend to take place during lumbar extension movements (Schendel, Wood & Buttermann, Lewis & Ogilvie, 1993). In lumbar extension, the lumbar extensor muscles exert a compressive force on the spine, which further adds to the facet joint loading (El-Bohy, Yang & King, 1989).

Based on the research mentioned above, and knowing that the facet joints are loaded at their highest in compression during lumbar extension movements (Schendel et al., 1993), repeatedly extending the low back on a shoulder press, deadlift, or roman chair hyperextension exercise is potentially going to create some issues down the road if repeated enough. Also, it’s no surprise to see such a high incidence of facet joint arthropathy in a sport like “tennis” that involves repetitive motions of lumbar extension and rotation (Alyas et al., 2007).

Additionally, it’s important to note that I played hockey for several years and many of those years at a competitive level. Ice hockey is a sport that involves repetitive lumbar extension and rotation, specifically seen during the ice hockey wrist shot, slap shot and snapshot. The repetitive motion from shooting overtime “likely” contributed to the development of my osteoarthrosis.

Also, performing a lot of exercises in the weight room with poor technique and compensating by going into lumbar hyperextension with high compressive load didn’t do me any favours and it’s a highly plausible reason “why” my osteoarthrosis developed.

The above photo represents poor (left) and good (right) technique performed on the Standing Barbell Shoulder Press. Hyperextension of the low back (left) repeated over time may beat up on the lumbar facet joints. Correcting hyperextension by maintaining a neutral spine is key in reducing the stress on the lumbar facet joints.

The above photo represents poor (left) and good (right) technique performed on the Nordic Hamstring Curl. Hyperextension of the low back (left) repeated over time may beat up on the lumbar facet joints. Correcting hyperextension by maintaining a neutral spine is key in reducing the stress on the lumbar facet joints.

Also, in a clinical setting, pain with lumbar extension/hyperextension (and rotation) has been purported to be a common pain-trigger associated with a symptomatic lumbar facet joint (Schwarzer et al., 1994; Schwarzer, Wang, Bogduk, McNaught & Laurent, 1995). It is estimated that about 15-40% of people with chronic low back pain arises from the lumbar facet joints (Schwarzer et al., 1994; Schwarzert et al., 1995).

Speaking from my own experience dealing with facet joint pain, lumbar extension/hyperextension did not respond well to my low back in the early stages of my recovery, and it is in part why I did not respond well to the classic “McKenzie” stretch to treat a lumbar disc herniation.

To this day, I still deal with some issues with regards to my lumbar facet joints, but they are pretty manageable for the most part. Prolonged sitting typically causes me some minor to moderate discomfort in my low back, but it is quickly relieved as soon as I stand up, walk around or lay down. The discomfort from prolonged sitting could be explained by the increased loading on the facet joints seen during prolonged static loading.

Under prolonged static loading, the discs begin to deform and expel fluid, which causes a change in the hydraulic system of the spine (Cheung, Zhang, & Chow, 2003). The discs become more flattened, and some of the compressive force shifts from the discs to the facet joints (Cheung et al., 2003), which could explain “why” my symptoms are triggered during prolonged sitting (increased stress on the facet joints).

The above photo represents what happens to the spinal discs during prolonged static loading as in the case of sitting. During prolonged periods of sitting (static loading) the spinal discs will expel fluid and become “flatter” in shape (bottom image), similar to how a water balloon may expel water. As a result of the spinal discs becoming flatter, there is a change in the way the spine system administers compressive force through the spine. The facet joints will absorb more compressive force as a result of prolonged static loading and loss of disc fluid (Cheung et al., 2003).

Aside from prolonged sitting being a bit troublesome, exercise such as squats when performed heavy have been challenging to work back too. The high compressive loading from heavy squats does not respond well to my low back, but other activities such as deadlifts are “okay” for the most part as long I perform them with near perfect technique and keep the rep range low.

Another thing that I’ve noticed that plays a big part in the management of my osteoarthrosis is sleep. I feel when I’m short on sleep or haven’t slept well in a few days, my osteoarthrosis symptoms (a backache, stiffness) may become a little more noticeable. When I get good sleep, I tend to feel like a million bucks, but if I’m short on sleep, my low back can be a bit of annoyance, specifically right after waking up.

While this condition has been a bit of a struggle at times, it has become manageable over the years from understanding spine biomechanics and identifying what works for my low back and what doesn’t. At the same time, as someone who thinks very optimistically, I’ve used this experience as a way of helping others work around or prevent similar lower back issues from developing.

All of the experiences that I have gone through have generated considerable interest for myself in the field of mechanically related low back pain, and it’s significantly helped with my understanding of the low back. Going through low back issues myself has made it much easier for me to understand everything from the anatomy, to the pain-triggers and the mental state of dealing with low back problems. As a result, instead of looking at this experience of being overall “bad,” I’ve used it as a way where I can help others in preventing or overcoming similar low back issues.

Also, about 8 out of 10 people will experience low back pain at some point in there life, and as a coach knowing statistics like this, you better have an understanding of how to work around a low back injury if you’re ever going to be successful with keeping your clients low back healthy (Fredburger et al., 2009).

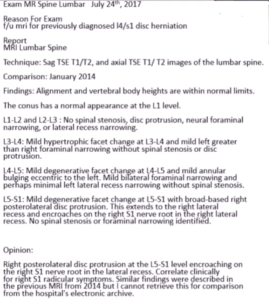

Finally, for my interest, I had a follow-up MRI conducted 3 and a half years later on my lumbar spine to see if any changes have occurred over the years. Here are the results:

The follow-up MRI report was conducted on July 24th, 2017. This is about 3 and a half years after my initial MRI. Note: This is not a true comparison considering a different radiologist examined my MRI images, and only the previous MRI report (no images) was available for examination by the radiologist.

Interestingly, in the follow-up MRI, changes seem to be present at the L1-L2 and L2-L3 levels, but degenerative changes still exist at the L3-L4, L4-L5, and L5-S1. Over 3 and a half years, there haven’t been many changes regarding my lumbar spine anatomy, but my symptoms have substantially changed and are manageable to this day as a result of implementing good spine sparing strategies.

Lesson Learned from Lumbar Facet Joint Osteoarthrosis:

1. Lumbar extension under compressive load should be minimized and avoided as much as possible for someone with existing facet joint osteoarthrosis. The lumbar facet joints absorb the most compressive force in a position of lumbar extension and if continually beat up on the facet joints by going into lumbar extension; you’re only asking for trouble.

2. It’s better to prevent degenerative changes from developing to the joint; rather than trying to rehab from them. Cartilage does not exactly heal quickly, and as you can see by my own MRI report, degenerative issues still exist after 3 and a half years.

3. Many athletes involved in extension based sports may develop degenerative changes to the facet joints of the lumbar spine at some point in their athletic career. As a result of this, it makes it even more important as a strength and conditioning coach to make sure athletes are not recreating the mechanism for this condition to develop in the weight room.

Exercise like supermans and roman chair hyperextensions may not be the best option for these athletes to develop the low back musculature. An alternative like the Bird-Dog, which places a lower compressive force on the low back (spares the spine) and produces similar muscular activation patterns when compared to the superman exercise and roman chair hyperextensions may be a much more effective option for developing the low back musculature (McGill, 1998; McGill, 2014).

4. Symptoms may be manageable if the mechanism of injury is removed and avoided. Avoiding lumbar extension under load is very important for anyone with extension based issues since this may recreate symptoms.

5. Sleep is crucial. Simply improving sleep quality can go a long way in helping manage symptoms since a lack of sleep may throw the circadian rhythm out of whack and impact the bodies physiology in a negative way that may aggravate symptoms.

While there is much to learn about the low back, I hope that my experience can help anyone out there in trying to prevent or work around low back pain.

Salute,

Remi

References

Alyas, F., Turner, M., & Connell, D. (2007). MRI findings in the lumbar spines of asymptomatic, adolescent, elite tennis players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(11), 836–841.

Cailliet, R. (2003). Low Back Disorders: A Medical Enigma. Philadephia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Cheung, J. T. M., Zhang, M., & Chow, D. H. K. (2003). Biomechanical responses of the intervertebral joints to static and vibrational loading: A finite element study. Clinical Biomechanics, 18(9), 790–799.

Dunlop, R. B., Adams, M. A., & Hutton, W. C. (1984). Disc space narrowing and the lumbar facet joints. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 66(5), 706–710.

el-Bohy, A., Yang, K. H., & King, A. I. (1989). Experimental verification of facet load transmission by direct measurement of facet lamina contact pressure.Journal of Biomechanics, 22(8-9), 931-941.

Fredburger, J. K., Holmes, G. M., Agans, R. P., Jackman, A. M., Darter, J. D., Wallace, A. S., Castel, L. D., Kalsbeek, W. D., Carey, T. S. (2009). The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(3), 8–9.

Jaumard, N. V., Welch, W. C., & Winkelstein, B. A. (2011). Spinal Facet Joint Biomechanics and Mechanotransduction in Normal, Injury and Degenerative Conditions. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 133(7), 0710101-07101025.

McGill, S. M. (1998). Low back exercises: Evidence for improving exercise regimens. Physical Therapy, 78(7), 754–765.

McGill, S. M. (2014). Ultimate Back Fitness & Performance Sixth Edition. Waterloo, Ontario: Backfitpro.com

Nielsen, M. & Miller, S. (2008). Real Anatomy 1.0. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Schwarzer, A. C., Aprill, C. N., Derby, R., Fortin, J., Kine, G., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine, 19(10), 1132-1137.

Schwarzer, A. C., Wang, S. C., Bogduk, N., McNaught, P. J., & Laurent, R. (1995). Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: A study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 54(2), 100–106.

Schendel, M. J., Wood, K. B., Buttermann, G. R., Lewis, J. L., & Ogilvie, J. W. (1993). Experimental measurement of ligament force, facet force, and segment motion in the human lumbar spine. Journal of Biomechanics, 26(4-5), 427-438.

Shirazi-Adl, A., & Drouin, G. (1987). Load-bearing role of facets in a lumbar segment under sagittal plane loadings. Journal of Biomechanics, 20(6), 601-613.

Skrzypiec, D. M., Bishop, N. E., Klein, A., Püschel, K., Morlock, M. M., & Huber, G. (2013). Estimation of shear load sharing in moderately degenerated human lumbar spine. Journal of Biomechanics, 46(4), 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.11.050

Yang, K. H., & King, A. I. (1984). Mechanism of facet load transmission as a hypothesis for low-back pain. Spine, 9(6), 557-565.

Tanchev, P. (2017). Osteoarthritis or Osteoarthrosis: Commentary on Misuse of Terms. Reconstructive Review, 7(1), 45–46.

Thumbnail Image Licensed from “Wavebreakmedia/depositphotos.com”

Video Licensed from “ozguyilmaz.hotmail.com/depositphotos.com”