Spondylolysis & Hockey Athletes

To follow up my previous post on lumbar disc herniation’s in hockey players, I thought it would only be fitting to talk about another common lower back injury in hockey players, which is spondylolysis. While not as common as lumbar disc herniation’s in hockey players, spondylolysis is still an injury that is relatively common and can cause a hockey player severe problems.

However, before we jump forward in this post, your probably wondering – what the heck is spondylolysis?

Well, let me explain.

What is Spondylolysis?

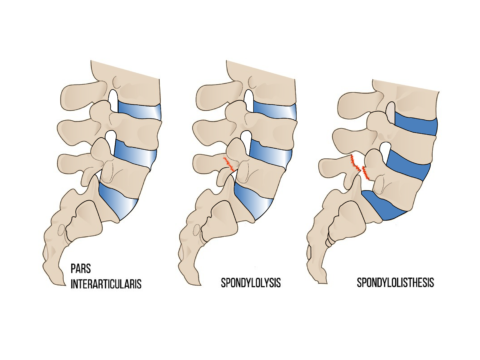

Spondylolysis is simply a term to describe a fracture or defect to the pars interarticularis (see Figure 1 below). It is most common at the L5 level, followed by the L4 level (Niggemann et al., 2011), which is similar to were lumbar disc herniation’s most commonly develop (Jordan & Konstantinou, 2009). The mechanism for injury involves repeated stress to the pars interarticularis that generally involves repeated lumbar hyperextension under axial load (d’Hemecourt, Zurakowski, Kriemler & Micheli, 2002; Leone et al., 2011). However, if you add spinal rotation into the equation, this could make things significantly more stressful onto the low back (d’Hemecourt et al., 2002; Leone et al., 2011).

As a result of this injury mechanism, it’s not uncommon to see spondylolysis develop in athletes that are involved in sports such as gymnastics, weightlifting, basketball, swimming, track & field (highest prevalence in throwing sports), and hockey (Donaldon, 2014; Soler & Calderón, 2000). Note: The one thing to point out about all of these sports is that they all have some of degree of lumbar extension and rotation involved.

Figure 1: The above photo represents a normal pars interarticularis, spondylolysis (middle), and spondylolisthesis (right). The pars interarticularis is a small piece of bone that connects the inferior and superior facet joint. Spondylolysis involves a fracture or defect to one or both of the pars interarticularis. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis involves the slippage of one vertebra over another and will usually start out as spondylolysis (Flowman, 2000).

To understand the injury mechanism a little bit better, I like to use swimming as an example for the casual reader when explaining spondylolysis. Swimmer’s whose main stroke is the butterfly or breaststroke have a higher incidence of developing lower back problems when compared to other competitive swimming strokes (Drori, Mann, Constantini, 1996; Nyska et al., 2000).

Both of these strokes involve moving into a position of lumbar hyperextension against resistance (water) and are often performed for upwards of a 1000 repetitions per training day (Nyska et al., 2000). Now, if you perform 1000 repetitions of the same swimming stroke each training day, that can become pretty stressful on the low back over time! Also, throw in a poorly designed weightlifting program, and you have just created a recipe for disaster!

Figure 2: Butterfly style and breaststroke swimmers are reported to have the highest incidence of spondylolysis when compared to other swimming styles (Drori, Mann, Constantini, 1996; Nyska et al., 2000). The repeated hyperextension of the lumbar spine as seen in the butterfly stroke above is purported to be the mechanism for developing a case of spondylolysis in swimmers (Drori, Mann, Constantini, 1996; Nyska et al., 2000). Licensed from “Vectorvstocker/stock.adobe.com”

Now, that you have got an idea of the mechanism for injury from the example of the butterfly style swimmer above, let’s move into the specifics of spondylolysis and hockey.

Spondylolysis & Hockey Athletes

Donaldson (2014) examined the incidence of low back pain in elite junior male ice hockey players between the ages of 15-18 years old from 9 seasons. Over those 9 seasons (44 players from 2 teams each season), 25 hockey players reported having low back pain with 11 of the 25 being confirmed lumbar spondylolysis cases.

Interestingly, 73% of these lumbar spondylolysis cases developed on the shooting side and 27% on the non-shooting side, with the majority developing at the L5 level, followed by the L4 level. It is believed the repeated twisting combined with flexion/extension seen during shooting is a contributing factor to spondylolysis for hockey players (Donaldson, 2014). The forceful twisting combined with flexion/extension being repeated overtime in a slap shot, wrist shot, or snapshot can likely beat up one’s low back over time. Also, it should be noted that the author mentioned these hockey athletes were performing Olympic style weightlifting, which when combined with repetitive shooting could of lead to a quicker onset of spondylolysis.

Figure 3: The Hockey Wrist Shot involves a combination of lumbar flexion (far left), trunk rotation (left, middle and right), and lumbar extension (middle and far right). The mechanism for developing spondylolysis is purported to be the motion of moving from lumbar flexion to lumbar extension combined with rotation (Donaldson, 2014).

Now, that we understand the purported mechanism of injury for spondylolysis in hockey players, as well as the incidence – what is the return to play like?

Well, unfortunately, there aren’t many documented cases in professional hockey and the research is pretty limited for hockey players at the moment. However, from the research available, Donaldson (2014) reported that the average time to return to playing hockey for these elite level junior hockey players with spondylolysis was 6-12 weeks, following physical therapy (core stabilization focus), and full rest from hockey/weightlifting. While this is a very small sample size and is not representative of the entire hockey population, it does seem to be more encouraging than the return to play after a lumbar disc herniation in hockey players.

With that being said, spondylolysis is still a devasting injury since a 2-3 month time span can cause a hockey player to miss a significant amount of time. It’s by far better to prevent this injury than ever have to deal with it and this leads me to my next question.

How Do We Prevent Spondylolysis in Hockey Athletes?

1. Follow a Properly Designed Strength & Conditioning Program

A poorly designed exercise program that may include exercises like loaded reverse hyperextensions, poor deadlift/squat/shoulder press technique, or any activity that may take the spine into lumbar hyperextension under load would be a no-no for hockey athletes. Repeated cycles of lumbar hyperextension are what is going to cause an injury like spondylolysis to occur (d’Hemecourt et al., 2002).

Like I’ve said many times before, do the right things in the weight room, and you can potentially add a few more years to your career as an athlete, whereas if you do the wrong things in the weight room, you could quickly end your career as an athlete.

Figrue 4: The left represents hyperextension of the low back and poor barbell shoulder press technique. Performing the barbell shoulder press technique on the left may lead to something like spondylolysis over time. Hockey players need to be specifically careful with this mechanism. The photo on the right represents good core-control and shoulder press technique. Notice how there is no hyperextension of the low back.

Figure 5: The photo on the left represents a poor Bulgarian split squat set-up technique (lumbar hyperextension). The photo on the right represents a good Bulgarian split-squat set-up technique (neutral spine). Avoiding any excessive lumbar extension under load is very important for a hockey player to prevent a future injury from developing such as spondylolysis.

2. Improve Hip Mobility

It’s no secret that hockey players have some of the stiffest hips and from my observation, they tend to almost always present with super tight hip flexors and a deficit in hip internal rotation. Many hockey players could benefit from specific mobility and soft-tissue work to their hip flexors, hip abductors and hip adductors.

Tight hips may lead to hockey players compensating and getting excessive movement in places that they probably shouldn’t (e.g., lumbar spine). Also, the link between alterations in hip range of motion and lower back pain has been well documented in several studies (Chesworth, Padfield, Helewa, Stitt, 1994; Ellison, Rose & Sahrmann, 1990; Vad et al., 2004). If a hockey player can get their hips moving a little bit better, it can a long way in sparing their low back, as well as their hips!

Figure 6: The above photo represents a Hip and Ankle Mobilization that exercise that involves keeping the back foot elevated, while the front knee rocks forward. A stretch should be felt along the back hip and a neutral spine should be maintained. Note: This is an exercise that I learned from Strength & Conditioning Coach and Athletic Therapist, Joey Garland.

3. Improve Anterior Core Control & Stability

Almost all hockey athletes live in anterior pelvic tilt, and this postural position may contribute to the onset of some lumbar extension based issues such as spondylolysis. However, a lack of ability to control for lumbar extension is where things can become problematic.

If an athlete can’t control lumbar extension properly, they may compensate by going into lumbar extension or hyperextension to get into a specific desired position (e.g., see figure 4 and 5). By going into lumbar extension/hyperextension, they may now be relying on more of their passive restraints (e.g., bone, ligament) to absorb force. Teaching athlete’s how to properly control their anterior-core, as well as improve their overall anterior core stability would be important in preventing a condition such as spondylolysis from developing.

4. Improve Rotatory Core Control & Stability

Hockey is a rotational sport, and many hockey athletes may lack the ability to control for lumbar rotation when performing twisting movements. As a result of this, hockey athlete’s may compensate by getting excessive movement at areas they probably shouldn’t (e.g., lumbar spine and similar to lacking anterior core control and stability), which may increase loading on specific tissues of the low back (e.g., L5 pars interarticularis and disc).

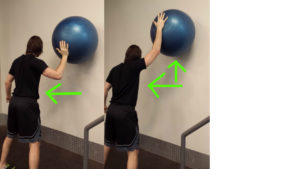

Incorporating rotatory stability exercises like the single arm stability ball push with scapular upward rotation, pallof press, bear crawl, and renegade row can go a long way in teaching a hockey athlete to control lumbar rotation, as well as helping them prevent a case of spondylolysis.

Figure 7: The Single Arm Stability Ball Push with Scapular Upward Rotation is a great “catch-all” exercise that involves rotatory stability (resist rotation), anterior-core control (resist lumbar extension), and scapular upward rotation (good serratus anterior recruitment). Note: Learned this exercise from strength & conditioning coach, Jon Lee.

5. Spend Less Time on The Ice During The Offseason

While this is easier said than done since every hockey player wants to improve their game continuously. Sometimes it may be best for some of these athletes to put the brakes on and allow for some time away from the game.

Almost all hockey athletes live in anterior pelvic tilt, and by continually being on the ice all the time, they are only going to develop further this asymmetry of the pelvis (e.g., developing excessive anterior pelvic tilt), which may possibly predispose them to a higher risk of spondylolysis (e.g., live in excessive lumbar extension from anterior pelvic tilt). By getting some of these hockey athletes off the ice during the offseason, we can focus on improving other hockey performance related variables like playing posture, power and shooting/skating mechanics.

Conclusion

There is a lot that hockey players can due to ultimately avoid developing a case of spondylolysis, and these are just a few important considerations I mentioned above. If you can follow these points above or begin to learn about the spine, it can go a long way in preventing a serious spinal injury from occurring.

Overall, the biggest area of concern too me is the weight room since this is an area where problems tend to develop or existing problems may become symptomatic. I specifically beat up my low back pretty bad from doing the wrong things in the weight room, and as a result, my low back will never be the same again. Point being, be very careful about what you do in the weight room because if you don’t, it will come back to haunt you one day.

References

Chesworth BM, Padfield BJ, Helewa A, Stitt LW. (1994). A comparison of hip mobility in patients with low back pain and matched healthy subjects. Physiotherapy Canada. 46(4), 267–274.

d’Hemecourt, P. A., Zurakowski, D., Kriemler, S., & Micheli, L. J., (2002). Spondylolysis: Returning the athlete to sports participation with brace treatment. Orthopedics, 25(6), 653-657.

Drori A, Mann G, Constantini N. (1996). Low back pain in swimmers: is the prevalence increasing? The 12th International Jerusalem Symposium on Sports Injuries, 75.

Ellison, J. B., Rose, S. J., & Sahrmann, S. A. (1990). Patterns of hip rotation range of motion: A comparison between healthy subjects and patients with low back pain. Physical Therapy, 70(9), 537-541

Floman, Y. (2000). Progression of lumbosacral isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. Spine, 25(3), 342–347.

Jordan, J., & Konstantinou, K. (2009). Musculoskeletal disorders. Herniated lumbar disc. Clinical Evidence, 3, 1–34.

Leone, A., Cianfoni, A., Cerase, A., Magarelli, N., & Bonomo, L. (2011). Lumbar spondylolysis: A review. Skeletal Radiology, 40(6), 683-700.

Niggemann, P., Kuchta, J., Beyer, H. K., Grosskurth, D., Schulze, T., & Delank, K. S. (2011). Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: Prevalence of different forms of instability and clinical implications. Spine, 36(22), 1463–1468.

Nyska, M., Constantini, N., Calé-Benzoor, M., Back, Z., Kahn, G., & Mann, G. (2000). Spondylolysis as a cause of low back pain in swimmers. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 21(5), 375–379.

Soler, T., & Calderón, C. (2000). The prevalence of spondylolysis in the Spanish elite athlete. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(1), 57–62.